Digital Ghosts

Paul Thorel Prize for digital arts at Madre Museum in Naples

Once, concepts like the digital afterlife were strictly the domain of religion or rather science fiction. Then came Charlie Brooker’s series Black Mirror, and suddenly the dystopia it exposed on the small-screen didn’t feel so sci-fi anymore. In the acclaimed episode Be right back, for example, Brooker tackled the emotional consequences of bringing back to life the deceased through high-tech solutions, as an act of love and denial[1].

Yet, since the creation of the first virtual memorial park, the World Wide Cemetery in 1995 by Mike Kibbee, Transhumanists—an ever-expanding community of techno-enthusiasts exploring the enhancement of the human condition by way of technology—have come a long way. So have AI, bio-robotics and surveillance, and now plenty of ideas involving immortality are in Beta phase, tested by millions of users.

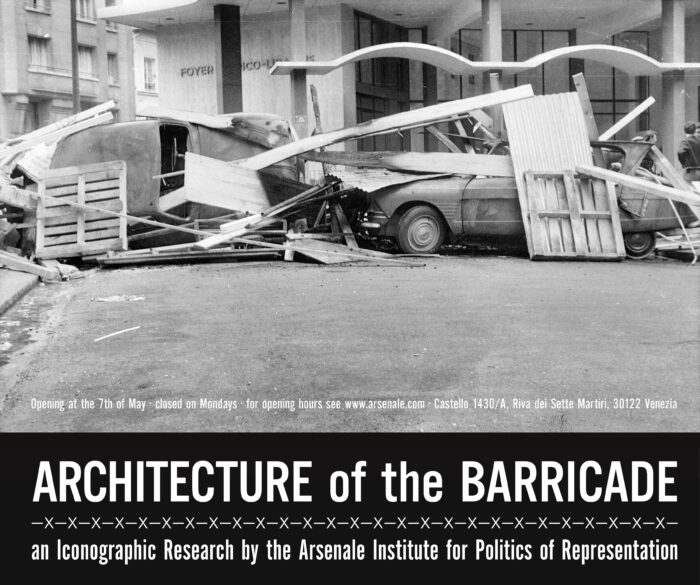

In Digital Ghosts, the exhibition of the second edition of the Paul Thorel Prize for digital arts at Madre Museum in Naples, the afterlife intersects with issues of circulation in cyberspace, new—profane, defiant?—iconographies prompting the question of whether a difference between digital human and inanimate ghosts even matters today, given that identity, trademark and copyright are all equally out of our control.

In the works of three artists—Anna Franceschini, Alterazioni Video, and Eva & Franco Mattes—encountered in this order through the rigorous room sequence of the Palazzo Donnaregina which houses the Madre museum, one finds a path towards the progressive dematerialization of signifiers which will dissolve as icons into the global infosphere. This digital, generative realm overflows into the analog world, the domain of the material and the tangible.[2]

The onlife contamination, between online and offline realities, reveals an unprecedented and, to some degree, egalitarian condition shared by humans, machines, and objects, both new and old actors within the collective imagination. As their presence proliferates across living rooms, shop windows, and screens, they are simultaneously transfigured into digital ghosts, entities suspended in a present that feeds upon—and in many respects converges with—the past.

Digital ghosts do not die, and their traces are not erased. Pixel-based images circulating on social media, websites, and blogs are copied onto remote servers and fed to artificial intelligences to generate content from the techno-symbiotic interaction between the human and the non-human. Digital death expert Davide Sisto describes a world in which copyright and consent no longer hold sway. We are all, he writes, “permanently available to posterity, and thus accidentally capable of living forever—cumbersome witnesses to the passage of death and the contemporary impossibility of disappearing and of forgetting.”[3]

Anna Franceschini’s works are inhabited by objects, souvenirs, and machines—stand-ins for a capitalist society that has silently infiltrated our lives, fostering an empathetic and sentimental connection. The artist draws upon an aesthetic of enchantment, the same visual and emotional strategy used to promote commodification and mass consumerism, while emphasizing the chains of value production, the role of display, and the circulation of goods.

In the exhibition, the sculptural bodies revered by the history of art and architecture, alongside the prosthetic figures of the celebrated Neapolitan nativity scene, no longer function as memento mori—symbols of transience and mortality—but instead serve as dynamic mediators of a reciprocity between life and death, grounded in the convergence of ritual, economy, and the humanization of digital experience.

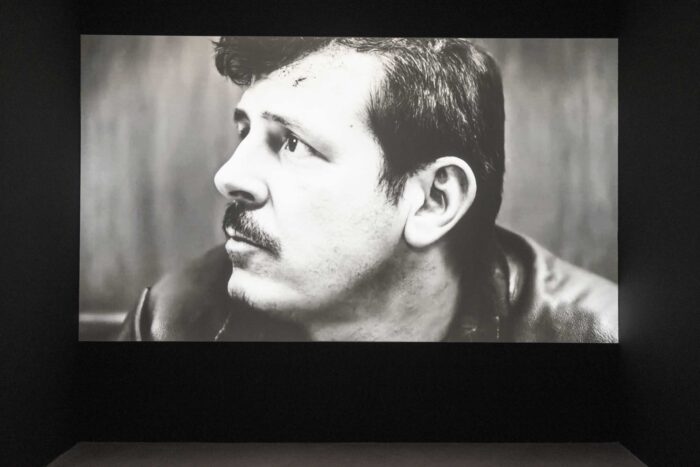

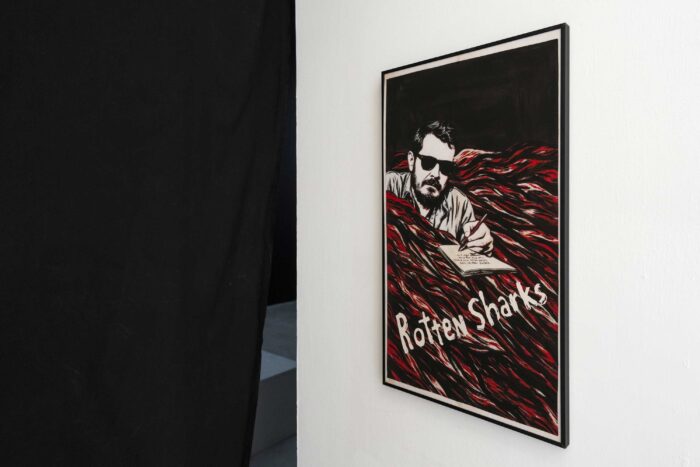

Alterazioni Video explores the hybrid and blurred territories of post-truth, YouTube neorealism, and deepfake technologies. It is a dissonant project, resisting the ideological standardization of populist thought that has permeated every sphere of society, striving for emancipation from the powerful forces that once controlled and disseminated culture before the digital and internet revolutions. The film, along with a series of memes and portraits, casts light on the writer and performer Filippo Anniballi, who died prematurely, and the lives he never lived.

The artist becomes the unwitting revenant of the digital world, amplified by AI and resurrected in a fictional Iceland he had imagined as the setting for his unfinished screenplay. The film is a distilled narrative animated by pirates and con artists, a “Rape of the Sabine Women,” and an idea of beauty that is both sensual and besieged. The portraits, meanwhile, merge the biting irony of internet culture with an emphatic painterly gesture in a commercial style that has been emptied of its former artistic value.

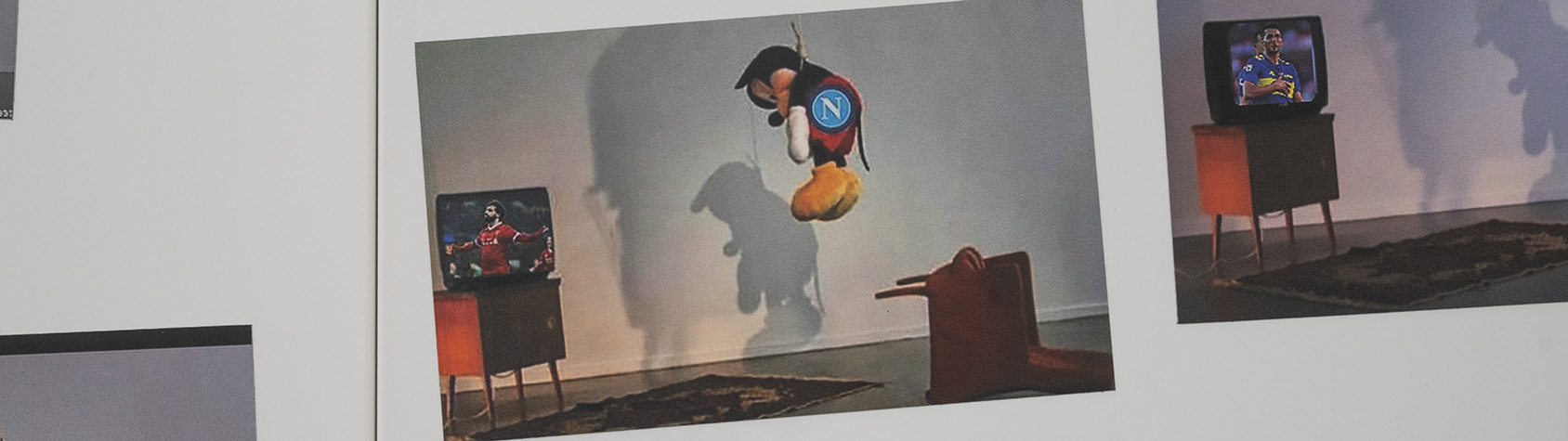

Eva & Franco Mattes expose the loop between visibility and invisibility that underpins the mechanisms of surveillance and the monetization of personal data across the internet and social networks, as well as the viral nature of contemporary imagery. Attached to magnetic boards in hypothetical office spaces—environments where boredom proliferates—are one hundred memes created by anonymous users based on a work by the artists. The image shows Mickey Mouse, innocent yet hegemonic icon of American pop culture, hanged in front of an old television set.

In this hallucinatory present condition embraced by the three artists, the immortality imposed by the information society produces a kind of digital purgatory of images, a radical space in-between in the infinite loop that existence has become for both things and people.