Diathomee

Sonic Underworlds Hailing From Lake Como

Anchored in a profound connection to the natural world and the landscapes of Lake Como, Sam Sala is an Italian producer, composer, and percussionist whose practice traverses the boundaries between sound, image, and materiality. His work unfolds through meticulously crafted compositions that combine lo-fi drones, field recordings, and modulated percussive elements, generating complex rhythmic frameworks and nuanced ambient textures. Now based in Brussels, he continues to refine his hybrid audiovisual language, exploring the tension between structure and instinct, control and chance. His debut solo project, Diathomee, draws inspiration from the microscopic world of fossilized algae and the broader ecosystems they sustain, weaving together organic textures and digital processes into a sonic reflection on time, erosion, and transformation.

On November 5, Sam Sala will present an exclusive premiere on Radio Alhara, featuring a live performance that offers a first glimpse of the experience he will later bring to the stage. The album will be released on November 10, marking the full unveiling of Diathomee and its immersive sonic world.

In this conversation, we explore the poetic interplay between sound and image, the dual forces of nature that inform his practice, and the emotional space that arises from being “in between”—between landscapes, between gestures, and between what is meticulously composed and what is allowed to unfold.

Clara Rodorigo: What idea first inspired Diathomee? And how do you approach sound as a conceptual and symbolic medium?

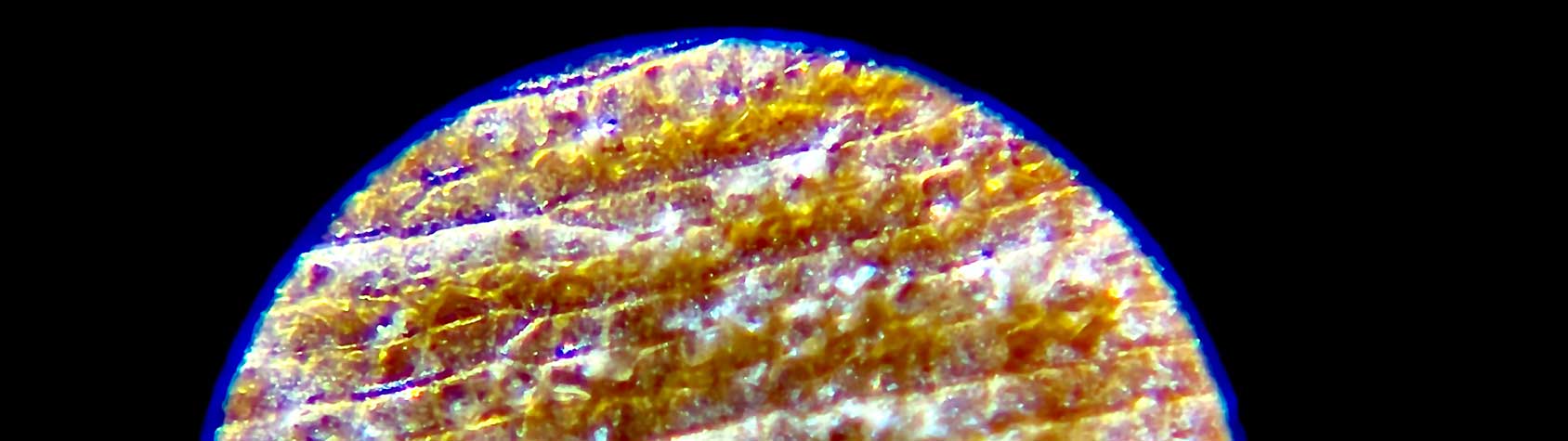

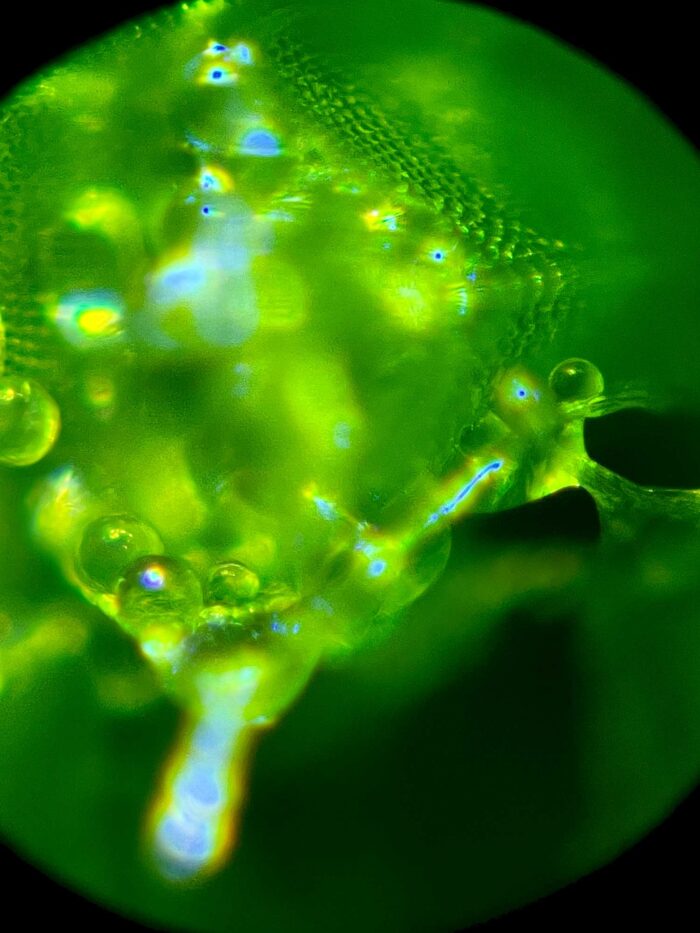

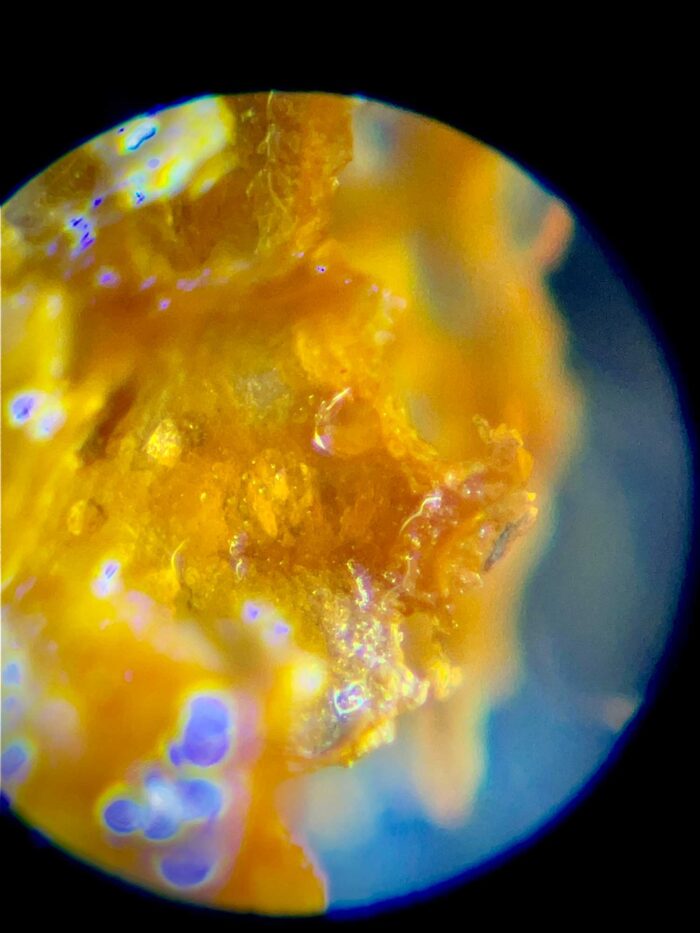

Sam Sala: Conceptually, Diathomee refers to fossilized microalgae—organisms that still inhabit oceans and freshwater environments, forming the foundation of the marine food chain. I was fascinated by the idea of something microscopic yet essential, invisible yet vital. There’s a clear parallel between these algae—the rhythmic base of an entire ecosystem—and the rhythmic structures in my music, which act as a kind of skeleton, the core framework of each piece. I deliberately altered the original spelling to Diathomee, adding an “h” to evoke the idea of home—a personal, protective space that feels safe and distant from judgment or inadequacy.

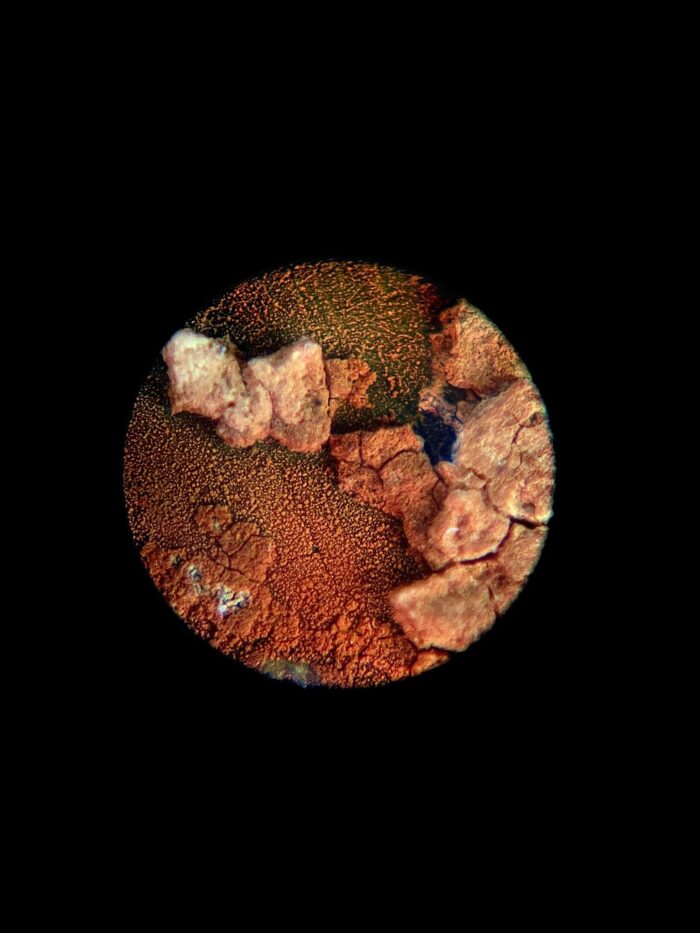

Visually, my project also recalls a natural phenomenon known as “sand rain,” when winds carry fossilized diatoms from African deserts across continents. This image of ancient, fragile matter traveling through time and space became a symbolic reference point for the album. The cover artwork evokes the vision of an old, sand-filled car—a small, imagined microcosm that mirrors the same sense of erosion, time, and transformation that runs through the music.

Clara Rodorigo: Your practice intertwines sound, visual art, and scientific inquiry, drawing on natural elements and organic processes. This interplay creates a poetic, almost tactile dimension of sound. From which of these realms does your practice emerge, and to what extent can it be understood as a material expression of the interdependence between visual and auditory perception?

Sam Sala: The project stems from my roots: a desire to create visuals with a strong connection to the natural world and to the places I come from—the mountains, the lake, the woods. I’m constantly drawn to these environments, and that ongoing contact has led me to build an extensive photographic and video archive.

My research often begins with small observed details—insects, textures, or overlooked objects—as a way to explore the invisible organisms and microstructures that shape the natural world. This process allows me to translate my curiosity for these hidden forms into sound and image, merging their tactile and organic qualities into a cohesive, sensorial language.

Clara Rodorigo: You approach the landscape of Lake Como as an archive of memory and cyclical transformation, where life and decay coexist in harmony. How do these natural dynamics shape the structure of your compositions and contribute to creating dense and dark atmospheres? Since moving to Brussels, has your sonic approach changed in response to your new surroundings?

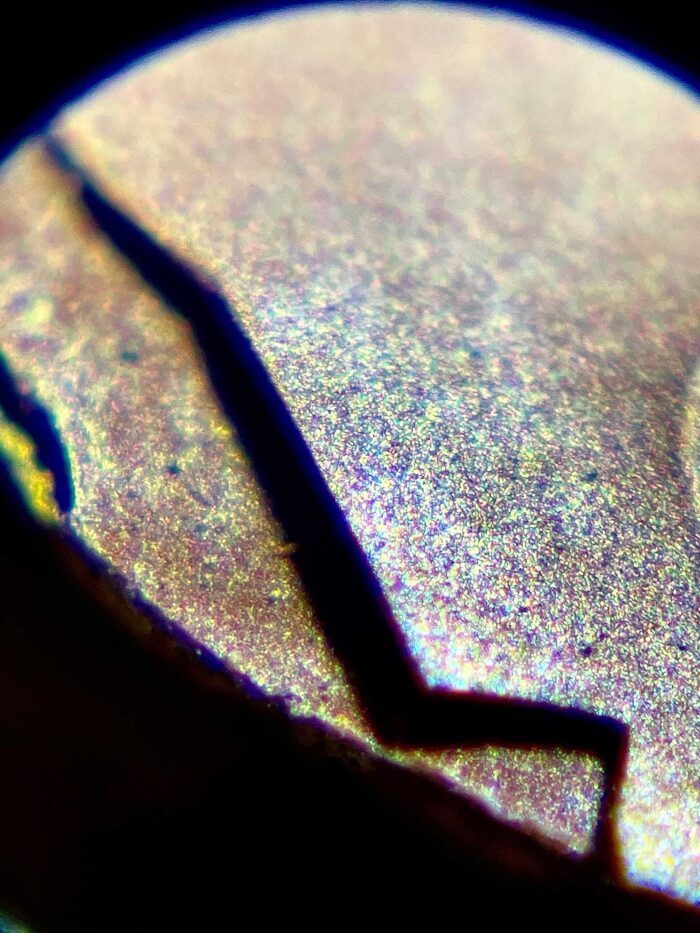

Sam Sala: I have always experienced nature from two very different perspectives, and this duality profoundly shapes my work. On one hand, there is the ethereal—light, greenery, and a sense of calm openness—and on the other, a darker, more violent, and silent dimension. These contrasting forces coexist in constant tension within my sound, shaping its density, its fragility, and its emotional depth.

The lake environment, which is very different from the sea, has always embodied this contrast for me. It can be serene and contemplative, yet it hides an underlying danger, a sense of stillness that can suddenly turn into violence. When I was a child, my grandfather was pulled into a whirlpool in the lake—an episode I never witnessed, but which has become a sort of family myth, an image that continues to define my perception of that landscape. The video for Birds, directed by Tommaso Tagliaferri, draws directly from that memory. Entirely filmed underwater, it captures the dual nature of the lake—at once nurturing and destructive, intimate and unsettling.

Brussels, where I now live, carries a similar kind of tension. It’s a dark, chaotic city— messy, raw, full of strange objects and unexpected energy. The album itself was conceived two years ago, so the move isn’t directly reflected in it, but the city is influencing what I’m creating now: sounds that are more obsessive, gritty, and chaotic, shaped by this new environment.

Clara Rodorigo: The concept of “soundscape” in your work reflects natural landscapes at every scale—from broad, macroscopic rhythms to imperceptible microscopic details. How do you work with these hidden layers to develop a sonic philosophy that connects microcosm and macrocosm?

Sam Sala: My approach is instinctive—I don’t really analyse emotions while creating; that comes later. It usually starts from quick sonic sketches, following whatever sound captures my attention—the crack of ice, the vibration of a surface, or a random found object. I work mainly with analogue instruments because they provide tactile feedback, a physical

connection that helps me shape texture and density. I’m drawn to layers—the imperfections, the “dirt,” the accumulation of sonic material that makes a track feel alive.

Conceptually, I’m fascinated by materiality—the same quality I find in the work of artists like Russell Mills, Antoni Tàpies, Alberto Burri, and Aldo Tambellini. I try to translate that into sound: gestures that are physical, surfaces that accumulate marks, and sonic forms that evoke both microscopic detail and vast, landscape-like movements. It’s a dialogue between scales—where the micro informs the macro, and the macro gives meaning back to the micro.

Clara Rodorigo: Your work moves fluidly between precision and instinct, alternating between structured rhythmic forms and improvisational moments where chance takes over. This dynamic reflects a broader tension in your practice—the sense of belonging versus existing “in between.” How do you navigate the interplay of control and unpredictability in your creative process, and how does this liminal space inform the emotional and spatial qualities of your compositions and performances?

Sam Sala: For me, control and chance are not opposites but parts of the same movement. I build rhythmic frameworks that act as a skeleton—much like the diatoms forming the invisible structure of marine ecosystems—but within those frames, I leave space for intuition, for gestures that can escape control. Improvisation keeps the work alive; it allows sound to breathe, mutate, and find new directions that I could never fully plan. Structure, on the other hand, provides the grounding that gives meaning and form to that freedom.

I see composition as a physical process, a dialogue between precision and raw gesture, between the microscopic and the monumental. Some elements are carefully constructed, while others arise from accidents—a texture, a feedback, a vibration that suddenly shifts the balance. That friction between what’s intended and what unfolds on its own is what gives the music its emotional depth and sense of instability.

This approach also comes from my background in bands and orchestras, where music is always a shared, performative act. Even now, with my solo setup—a computer combined with analog instruments like the Minibrute and the percussive Soma—I need to feel that same physical connection. I don’t want to stand still behind a screen; I want to play, to move, to let each performance become slightly different from the previous one.

Maybe it’s a kind of resistance to the idea of control—or maybe it’s the space “in between” where I feel most at home. That liminal state, where sound is both fragile and forceful, precise and chaotic, is where I find the most honest form of expression.