Cartographies of the Unseen

On Coco Fusco’s retrospective “He aprendido a nadar en seco” at MACBA – Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona

MACBA unveils the beating heart of Coco Fusco’s practice through a retrospective that sketches a critical landscape where bodies, stories, and dissent become forms of resistance. What emerges is an intense and revealing journey through thirty years of radical practice, in which the archive turns into resistance and art becomes an act of political responsibility.

“Although I have labored in the shadow of the flawed multiculturalist discourses that shaped American cultural debates for more than three decades, I have never made my artistic practice into a search for my roots or an exploration of selfhood as distinct from the world. The labels that many insist upon to define themselves interest me much less than the systems of power and knowledge that delimit identity and the relational networks we activate to communicate, resist, and make new meaning. So much of my endeavor over the past three decades has been devoted to relaying, recalling, interpreting, and embodying those who have occupied the place of the other in Western culture. To considering the presence and absence of others. To interrogating otherness, unmasking the practices of subjection that undergird seemingly genteel appreciation of diversity. In the territories where I roam, fictions cannot be disentangled from reality or truth. Fictions that attract us also weigh upon us, and once we invest in them as truths they can never be completely dispelled. I carry their weight when I assume the role of an ethnographic oddity, or a posthuman scientist, or a survivor of colonial massacres, or prisoner of postmodern warfare, or a subaltern service worker peddling fantasies for tourists. and assembling trinkets for insatiable consumers. The beings I temporarily inhabit are specters that emerge from unaccounted histories, all bearing inconvenient truths. They haunt me, but in a good way. I haunt you with them.”

Plaza de la Revolución in Havana is a space of sleepwalking, one of the darkest and most hypocritical remnants of an unfulfilled revolutionary dream. Flanked by the towering iron outlines of revolutionary martyrs Camilo Cienfuegos and Che Guevara, and watched over by the central marble statue of the idealized father of the nation, José Martí, the raw, inhospitable arena is now home to more nesting vultures than citizens.

In the video La Plaza Vacía (2012), Coco Fusco sharply and lucidly captures the ambiguity of this place, one of the most iconic sites of revolutionary Cuba. Filmed in the wake of the 2011 Arab Spring, the documentary raises urgent and uncomfortable questions: why does this square, once the beating heart of Castro’s ideology, now echo with silence? Why was there no “Cuban Spring”? What was lost with the institutionalization of the revolution?

This work can be considered a key to interpreting the artist’s full trajectory; born in New York in 1960 to a Cuban mother, Coco Fusco has spent over three decades practicing a kind of “politics of discomfort,” digging into the shadow zones of power, the languages of propaganda, and the strategies of erasure. With a gaze able to penetrate the opaque veil that the regime weaves to shield itself from external interference, the artist makes visible what remains hidden beneath absences, contradictions, and censorship.

At the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA), the large retrospective He aprendido a nadar en seco offers an opportunity to step into the core of this perspective. Taken from a 1957 poetic text by Virgilio Piñera, the title evokes a condition of forced adaptation, a deep and silent survival that encapsulates a certain tension between speech and silence, the subversion of language, and the ongoing friction between artistic expression and power—both past and present.

Curated by Elvira Dyangani Osé and organized in collaboration with El Museo del Barrio in New York and the Ford Foundation, the exhibition brings together over one hundred works, including videos, installations, drawings, texts, and archival materials, divided into five thematic sections. This figures as a chance to immerse oneself in the work of an artist who has consistently looked at the world from an uncomfortable yet essential vantage point, always foregrounding the necessary questions. Questions that expose a wide array of themes aimed at challenging dominant positions, dismantling racial stereotypes, deconstructing gender politics, revealing cultural biases, and surfacing decolonial narratives and untold or suppressed histories. Fusco’s long career as an interdisciplinary and conceptual figure occupies these very spaces, using performance to explore the complex ways bodies are shaped by power.

land, 2025. Photo Roberto Ruiz.

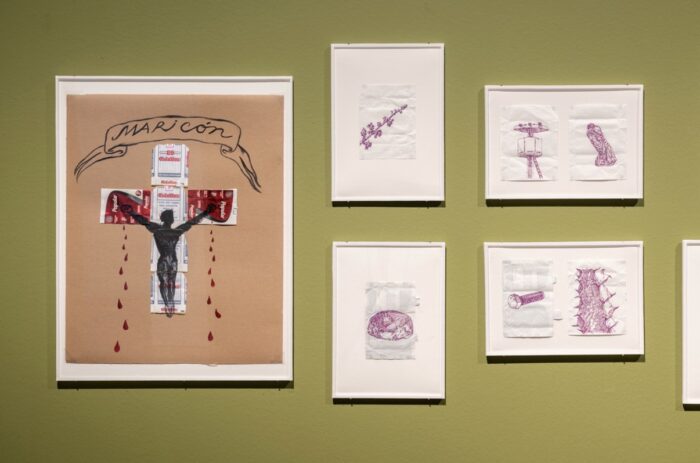

In her more recent works, the artist continues this critical investigation, using video and performance both to respond to the Cuban state—facing censorship and travel bans as a result—and to bring to light an archive of dissident practices. The first section of the exhibition features works dedicated to figures like Heberto Padilla (La Confesión, 2015; La Sombra de Herberto Padilla, 2021), María Elena Cruz Varela (La Botella al mar de María Elena, 2015), and Reinaldo Arenas (Vivir en Junio con la Lengua Afuera, 2018), as well as the project Confidencial: Autores Firmantes (2015), which reconstructs the physical and symbolic spaces of repression. Fusco documents locations in Havana emptied by political violence, such as the building where Padilla was forced to confess and the site besieged during the crackdown on Cruz Varela.

When attempting to film Arenas’ refuge, she was denied entry to Cuba and declared “inadmissible” without explanation—turning censorship itself into a key part of the narrative: that of a country built on erasure and control, where parks and plazas appear open but are in fact surveilled, silenced, closed off.

Through these gestures and images, Fusco reactivates such places as sites of counter-memory, making visible the absences, exclusions, and ghosts suppressed by the regime. In this erased context, the solitary presence of the artist’s body questions the very possibility of individual agency under such pervasive power.

However, individual actions often turn into collaborative ones, a central element in Fusco’s practice. Her work extends beyond personal creation, nourished instead by shared aspirations and long-standing alliances. Between the late 1990s and early 2000s, Fusco developed a series of incisive projects with performer Nao Bustamante, exploring the critical intersections of identity, gender, and power. Stuff (1996–99), for instance, is a sharp action on globalization, tourism, and sexism; while the photo series Paquita y Chata (1996) features the two artists embodying the Mexican papier-mâché Lupita dolls, traditionally associated with prostitution, subverting such stereotypes with irony and awareness.

This same reflection on alterity is central to a major focus in the second section of the exhibition: the touring performance Couple in The Cage: Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West (1992–94). Created in collaboration with artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña, the piece exposes the persistence of colonial fantasies in contemporary cultural consumption. Fusco describes this “living tableau” as the first true intercultural performance, capable of laying bare what she calls the “colonial unconscious”: an invisible yet pervasive system of representing and consuming the Other. This insight anticipates the work of theorists like Aníbal Quijano on the “coloniality of power,” forcing us to confront how deeply colonial structures continue to shape contemporary imaginaries.

land, 2025. Photo Roberto Ruiz.

A significant portion of the performances and videos in the exhibition lay bare the workings of power—from the repressive forms of the prison system to the mechanisms of policing and control.

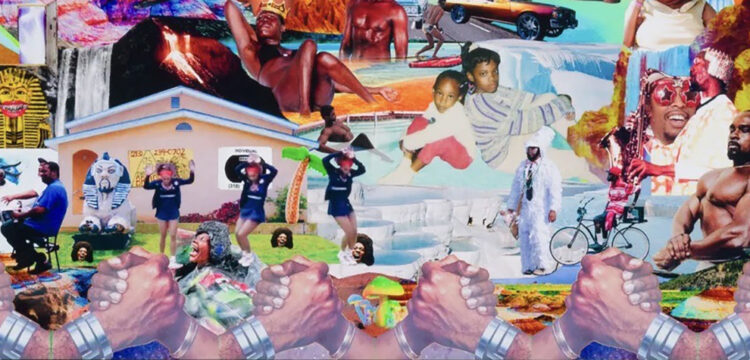

Within this context is Aponte’s Lost Podcast (2025), one of Fusco’s most recent and powerful works, produced for MACBA in collaboration with Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, a Cuban artist and activist imprisoned in the maximum-security facility of Guanajay. A leading figure in the San Isidro movement and the author of the protest anthem slogan Patria y Vida—a sharp reversal of the iconic “Patria o Muerte” that still adorns walls across Cuba—Otero continues to draw daily in prison but is forbidden from exhibiting. To break this censorship, Fusco invited him to describe his works over the phone. The recordings were then shared with a network of artists who reinterpreted them as drawings using basic, improvised materials such as ballpoint pens and cigarette packs—the same ones available to inmates.

The installation draws inspiration from the historical figure of José Antonio Aponte, an Afro-Cuban artist and revolutionary executed in 1812 for organizing a slave revolt. His drawings were destroyed, but their descriptions survived through inquisitorial interrogation records. Then, as now, the word survives oblivion, returning as image, resistance, affective and political archive. Aponte’s Lost Podcast is not just a reflection on the prison as a space of oppression, but a practice of collective imagination that transforms distance into connection, absence into visibility, and art into a pure act of disobedience.

With He aprendido a nadar en seco, Coco Fusco does not merely deliver a retrospective, but constructs a critical landscape in which art, memory, and dissent intertwine within an active, deeply political curatorial device. This is further affirmed by the final part of the exhibition, the Fusco Archive. This section does not merely collect documents: it reactivates and transforms them into tools of resistance against oblivion and systemic invisibilization.

land, 2025. Photo Roberto Ruiz.

The exhibition concludes with three powerful works made in collaboration with artist and activist Loid Der—Environmental Activists Assassinated Worldwide (2023), Journalists Killed at Work Worldwide (2023–24), and Artists in Prison Worldwide (2024). A moving cartography of risk, these works restore voice and dignity to figures often erased from official narratives. This choice archives erasure itself, exposing the silencing of those who act from the margins, offering not just data, but an ethics of memory. Here, art is not presented as something decorative or didactic, but as a critical force that operates within and against the very systems that host it. This exhibition is not simply a journey through thirty years of militant artistic practice—it is a powerful moral and political call, one that opens cracks, generates friction, and, above all, demands responsibility.