A Biopatchwork

Achiropita: genderless and anarchic ecology in contemporary art

Davi Kopenawa, shaman of the Yanomami community, stated that urihi a, the forest-land, “is not a realm external to society, a mute and inert backdrop for human activities or a mere field of resources to be dominated. Rather, it is a vast living entity, […]” which cannot be understood as a surface bounded by closed frontiers and shaped by identity logics, but rather as a “system of land-values” in constant and ongoing rhizomatic recomposition. The biodiversity of the forest is the result of the sociodiversity that characterizes it: “[…] the interactions between humans in the strict sense and other animal species is, from the Indigenous point of view, a social relationship, that is, a relationship between subjects,” in which even stones play a social role: “the native logic attributes an intentionality to stones that allows them to be considered among the living beings, and this enables rock formations to relate to humans, triggering visible and documentable responsive behaviors.” Indeed, as Eduardo Kohn observed during fieldwork among the Runa of Ávila in Ecuador, forests “host other emerging loci of intention-meanings that do not necessarily revolve around humans and do not originate from them.” As the artist Daiara Tukano points out, in her people’s vocabulary the term mahsã (“people”) is also used to refer to non-human species: wai mahsã, the people of the waters—the fish; yunku mahsã, the people of the forest—the woods; nohkoa mahsã, the people of the stars. Therefore, as Kohn himself states, such relationships “come to share, with increasing intensity, a sort of trans-species habitus that does not observe the distinctions we would usually make between nature and culture.” Thus, in such contexts, ecology—whose language and discourses, according to Kopenawa, have always existed within his people’s cosmopolitics—should be understood starting from the sense of “home” it contains within itself (the term ecology derives from the combination of oikos and logos, home and discourse). The forest—and by extension the habitat—imposes a web of eco-relations, of essentially domestic interactions, which should not be understood in the derogatory sense of submission and hierarchy, but rather in terms of familiarity, of creating networks in which one is an extension of the other. To conceive of living space in this way means to build an anarchic ecology.

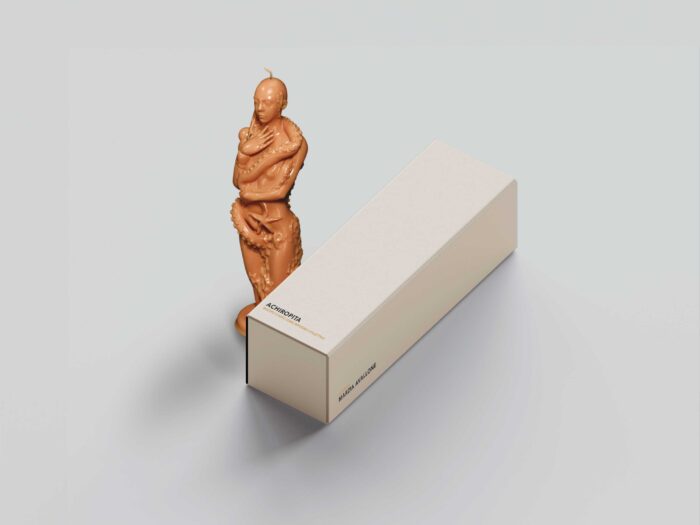

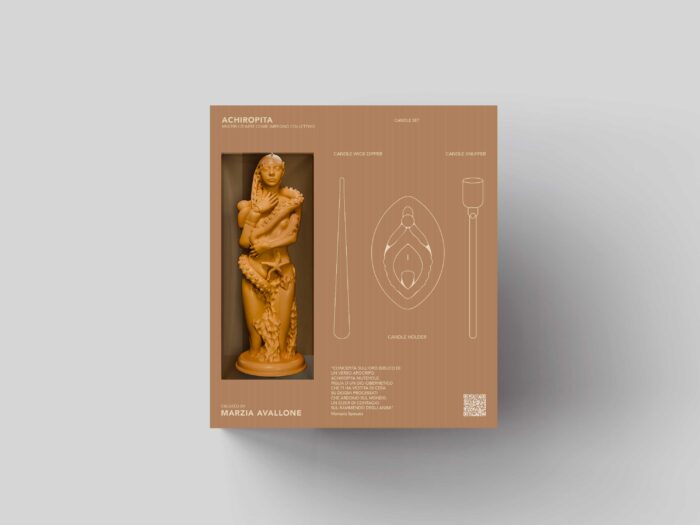

It is within this context that Marzia Avallone’s project takes shape. Achiropita (a term of Greek origin referring to artifacts not made by human hands and which appear unexpectedly, almost miraculously) seems to represent a contemporary goddess whose message echoes not only the tentacular life described by Haraway but also Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s warning, “when everything is humanized, everything becomes dangerous.” The object created by the artist, inspired by the Madonna della Salute in Venice, is a candle—perhaps, it reveals its truest meaning only through its burning. The goddess, in fact, presents herself as an assemblage of human, more-than-human, and mechanical elements, which, through the slow melting of wax, blend together into a single material that, like Simondon’s clay, already contains its own form. This simple process reveals three fundamental perspectives.

The first can be provisionally named biopatchwork. The survival of living beings can no longer be conceived on the basis of the individual characteristics and specificities defining each life form. To inhabit the ruins of the present, it is necessary to acquire and develop abilities that appear to belong to other animals or plants (during long hunting trips, the Yanomami use sound mimicry systems that allow them to locate prey).

The second point concerns gender. It is not only a matter of abandoning binarism—which would merely reaffirm its strategies by creating new identities that are different yet complementary to previous ones—but rather, as Deleuze and Guattari noted, of creating becomings, whether animal, vegetal, or non-human, in order to trace lines of flight. In some Indigenous cultures, the Western concept of “person” does not exist; instead, it is one possibility among many. For example, in the traditional Mapuche dance Choique Purrún, the dancer does not imitate an animal, but becomes it. As Antonio Catrileo states, “we are the multiplicity of greens in a forest that is never a monoculture. We open ourselves to vegetal time, to the grammar of chlorophyll, to perform photosynthesis with the sun.”

Finally, a third point corresponds to what we may call biophany. The artwork that aims to respond to the present, that seeks to engage with issues related to the ecological collapse resulting from expansionist, appropriationist, and extractivist policies of the Western world, must necessarily demonstrate the complementarity of humans and more-than-humans. The candle melts, and in its melting it fuses together animal, human, vegetal and mechanical elements. What remains is an accumulation of wax that reminds us of something other cultures know well—we are nothing but forces or intensities playing within the planetary theatre of cosmopolitics.

Leonardo Mastromauro: Dear Marzia, your work seems to be almost a visual transposition of Donna Haraway’s thought. How has the scholar’s thinking influenced your work?

Marzia Avallone: Donna Haraway’s thought runs through my work, though not in a derivative or didactic way. I’m not interested in visually transposing her theory so much as operating within the same field of tension where ontology becomes impure, situated, performative.

Her figure of the cyborg—more than a posthuman icon—influenced me as a narrative and ontological structure, capable of defusing epistemological dichotomies: subject/object, nature/culture, artifice/origin. In particular, I found her call to stay with the trouble essential, and I’ve internalized it as both a method and a critical stance.

The object-based art I’m developing within Achiropita is not a visualization of theory, but a form of material thinking. In this sense, my relationship with Haraway is more akin to an epistemic alliance than a citation. My objects don’t aim to illustrate Haraway, they want to dialogue with her. Perhaps even contradict her, when necessary. They don’t seek to resolve, explain, or represent, but to generate problematic co-existences, material disquiet, liminal zones.

A particularly significant reference for me is The Companion Species Manifesto, in which Haraway shifts the focus from technological to affective and interspecies hybridization. This opened up a reflection for me on objects not as tools, but as epistemic companions—agents with whom one co-thinks, coexists, and builds a shared history of ambivalences. My objects don’t “speak” for me, they make me question myself.

Lastly, I also find affinity with Haraway’s writing itself, which is always tentacular, oblique and contaminated. This has influenced the structure of the Achiropita project as a whole, which rejects closed authorship and instead proposes a transdiscursive ecology, where every nuance of the project is an unstable interface between matter, voice, and concept.

The candle seems to evoke the idea of a biopatchwork, a living being resulting from the assemblage of human and non-human parts. Can you tell us more about it? Do you believe this is the path we should take to face the eco-political catastrophes of contemporary societies? In that sense, do you think it’s possible to speak of a biological and ecological anarchy?

For me, the candle is a hybrid organism. A biopatchwork, as you suggest, though not in the sense of a being composed of assembled fragments—but rather as a body in continuous dissolution, where the parts do not stabilize an identity but show its transience. It is a living object because it is consumed. Because it exposes time. The dripping wax is its liquid memory. It is an object that dies, slowly, in public. In this sense, it is also a vulnerable device, staging the crisis of integrity—bodily, political, ecological.

I don’t think the human/non-human assemblage should be read as a fate to accept or reject. Rather, I see it as a condition that is already active, already real, and which artistic practice can bring to light with clarity and without rhetoric. The candle, in its porous materiality, is already a contaminated subject: animal, plant, mineral, cultural elements are in it. It is flesh and combustion. It is both ritual and ruin.

Regarding your question about responding to eco-political catastrophes, I don’t believe there is one direction. I do believe that abandoning the idea of purity—biological, identity-based, epistemological—is a necessary condition for beginning to think otherwise. In that sense, yes, I’m happy to speak of biological and ecological anarchy, if by anarchy we do not mean chaos, but a non-hierarchical coexistence of life forms, materials, agents. An ecosystem not based on order, but on relational complexity, on improper mutualism, on excess beyond function.

The candle does not represent this anarchy, it enacts it. And in doing so, it also reveals its pain, its loss, its impermanence. But perhaps it is precisely in this instability—in this slow combustion—that we can begin to imagine radical forms of shared responsibility.

Part of the proceeds will be donated to Survival Italia in support of their campaign for uncontacted peoples. As we know from anthropological studies, the issue of anti-hierarchical relationships between humans and non-humans—and the social role the latter play within the organizational structures of communities and their cosmopolitics—is fundamental to Indigenous logics. Why did you choose to support this cause? Is there a connection between the ways Indigenous peoples reflect on human/non-human relations and your work?

The decision to donate part of the proceeds to Survival Italia, specifically for the campaign supporting uncontacted peoples, arises from both a political and an epistemic urgency, the need to defend the possibility that radically different worlds from our own may exist—worlds that cannot be assimilated, narrated, or represented according to our categories.

In my work, the relationship between human and non-human is never neutral or decorative. It is a relationship that challenges the centrality of the human as the knowing and acting subject. In this sense, the cosmological and organizational systems of Indigenous communities—where animals, objects, plants, rivers often carry intentionality and social value—deeply question me. Not to be adopted, but to recognize that other ways of thinking about coexistence exist.

Supporting these peoples also means supporting an ontological diversity, not only cultural, but cosmopolitical, as Eduardo Viveiros de Castro would say. And that is precisely what interests me, not to represent alterity, but to make room for its “inassimilability.” The object-based art I practice does not seek to speak on behalf of, but to create spaces in which Western thought can be suspended, displaced, even wounded, if necessary.

In this sense, yes, there is a profound connection between my practice and Indigenous cosmologies, not in imitation, but in the desire to deactivate the hierarchies between the living beings and non-living ones, between nature and culture, between West and East, between body and object. Even if only for a moment, even if only through a formal gesture, an inappropriate material, a presence that resists permanence.

It is not appropriation, it is an alliance with that which exceeds us—and does not wish to be translated.

What do you think about what will remain of the candle once it has burned down? The wax melts, human and non-human parts fall together. What is left? Can we imagine that in that seemingly formless pile of wax lies, in some way, the true power of the work? In that melted wax where human and non-human blend, don’t you think there lies the possibility of a genderless life—in the sense of being without attributes, unclassifiable? And isn’t that precisely the message of the piece?

What remains of the candle after it has burned is, to me, the residual body of the work—its non-negotiable part, non-spectacular, unproductive, but full of meaning. It is what survives the exhibition device, linear time, and function. A formless deposit, yes—but not accidental. It is the geology of the gesture, the place where matter and intention met and then melted together.

The dripping wax—that heap which may seem like waste—is actually the point of greatest density in the work. Not because it contains a hidden message, but because it reveals what happens when the identity of the object implodes, when the human and the non-human are no longer represented, but collapse together into a matter that can no longer be interpreted through pre-existing codes.

In that molten mass, there is no neutrality, but excess. There is no absence of form, but form without a model. And perhaps yes, precisely at that point, where everything blurs and nothing can be traced back to a name, the possibility of an unclassifiable existence emerges. Not as a lack of gender or meaning, but as an excess that escapes all attribution.

If there is a message—or rather, a vibration—of the work, it is exactly this, a semiotic excess, an area of indistinction where matter no longer responds to the logic of representation but becomes pure ontological relation. It is in that wax—fallen, confused, no longer functional—that the residue does not signify, but insists on.

Your project draws inspiration from the figure of the Madonna della Salute. Can you tell us why you chose this reference and its genealogy? The choice of the candle seems to evoke the idea of the ephemeral—something destined to be consumed, leaving behind only a formless pile of wax. Can you explain why you chose to translate and materialize the project through this object?

The project draws inspiration from the figure of the Madonna della Salute because it’s an image that has accompanied me since childhood, though I’ve never experienced it in strictly religious terms. It has always struck me as a collective invocation device, a ritual gesture charged with precarity and reciprocity. Every November 21st, from the South to Venice, candles are lit, promises are made, bodies—one’s own and others’—are entrusted to an icon that is at once presence and threshold, figure and refuge.

This figure has a genealogy intertwined with the history of epidemics, care, and shared vulnerability. The Madonna della Salute is not a glorious or victorious saint, she is an image of collective survival, of residue, of negotiation between the living beings and the invisible. Achiropita was born from this—not as a devotional work, but as an attempt to question the matter of protection, what remains, what burns, what cannot be touched but must be crossed.

The choice of the candle as an object is not accidental. It is a body that consumes itself in order to be—that doesn’t leave a monument, but a residue. I was interested in this paradox, an object that lives in its own dying, that is not preserved but offered, that doesn’t assert but accompanies. The dripping wax, deforming, blending with human and non-human elements, becomes a threshold between the ritual gesture and the excess material, between the sacred and the relational.

Translating the project into a candle was, for me, a way to materialize the act of trust—in combustion, in time, in transformation. It is not an object that wants to last, but one that wants to stay—as long as it can. And in its staying, to become a site of contact, of shared fragility, of memory not fixed but happened.

Bibliography

Albert, B., Kopenawa, D. (2023), Lo spirito della foresta, nottetempo, Milano.

Borgnino, E. (2022), Ecologie native, elèuthera, Milano.

Catrileo, A. (2019), Awkan epupillan mew: dos espíritus en divergencia, Pehuén Editores, Santiago.

Kohn, E. (2021), Come pensano le foreste, nottetempo, Milano.

Viveiros de Castro, E. (2013), La mirada del jaguar. Introducción al perspectivismo amerindio, Tinta Limón, Buenos Aires.